Blog Layout

150 Years: A Legacy to Celebrate

Sep 07, 2020

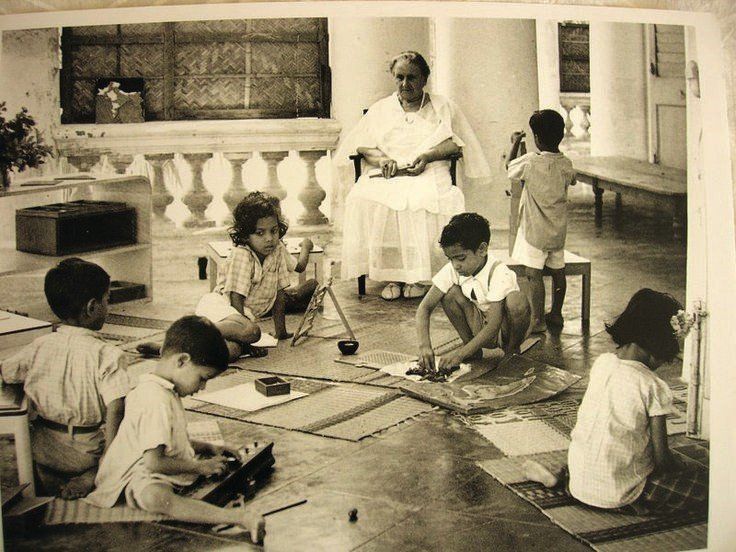

This article is part of a series that we will share throughout the 2020-2021 school year to celebrate the 150th birthday of Dr. Maria Montessori. Check back often for more posts that reflect on the past, present, and future of Montessori education.

August 31 marked the 150th birthday of Dr. Maria Montessori. Throughout the upcoming school year we will be bringing you articles in celebration of this milestone, kicking it off with a month full of articles this September.

First off, we would like to share a little bit about the woman herself, the course this remarkable educational movement has taken, and where we are today.

Education, Service, and Drive, From the Start

In a seaside town in Italy, Maria Montessori was born in August of 1870. At the time, education was not always readily available for girls and women, and was certainly not emphasized. Her father Alessandro was a man with fairly conservative views, but Montessori’s mother Renilde was rather well educated herself. Well into her young adulthood, Maria’s father often disapproved of her life decisions, while her mother encouraged them. (He did, fortunately, seem to have a change of heart later on.)

Even as a child, a deep sense of service was instilled in Maria by her parents. She knitted for and spent time with those in her community that were less fortunate. She was tasked with cleaning the floor of her family home, a chore which she likely took great pride in.

Maria’s family moved when she was young due to her father’s work, and they eventually ended up in Rome, where she began the first grade. Schools in Rome at the time were far superior to those elsewhere in Italy, so her educational advantages began early.

At a certain point, school and learning became much more important to Maria. It is said (and referenced in a biography by Rita Kramer)

that she once took a math book with her to the theater so she could study during the performance. One thing she was certain of: she would never become a teacher.

For a while, young Maria aspired to be an engineer, but later decided she would rather attend medical school. At the time (unfortunately but perhaps unsurprisingly) women were not permitted in the university program. Not to be dissuaded but an initial rejection, Montessori took and passed the entrance exams and continued to ask for admittance until she received ‘yes’ for an answer.

During her years at the university, Montessori faced constant discrimination due to her gender. She was not permitted to enter lecture halls at the same time as her male counterparts or study cadavers alongside the other medical students. (They felt it improper to be in the presence of a dead, naked body with a woman.) She wasn’t even allowed to walk to school without a male chaperone, who was, of course, her disapproving father.

Despite it all, Maria Montessori did become Dr. Montessori. Over the years she gained the respect of many of her university peers, faculty, and family members.

A Winding Path to a Visionary Model

Early in her career, Montessori was assigned to work in a psychiatric hospital. Children were treated there alongside adults, and Montessori was struck by the sheer lack of stimulation available to the children. She began working with the children and soon realized their cognitive capabilities far exceeded what they were assumed to be able to accomplish.

Not long after, Montessori was asked to start a school in an impoverished neighborhood in Rome. In an apartment complex, the parents were forced to go to work each day and leave behind their children who were too young to be in school yet themselves. This led to a natural progression of unruly behavior, thus leading the apartment manager to seek a solution.

Montessori opened her school on the first floor of one of the apartment buildings. It was called Casa dei Bambini (Children’s House) and provided a place for the little ones to use their time productively, while also allowing Dr. Montessori an opportunity to develop her now infamous materials and methods. She believed that young children learned first through the senses, and her materials were created specifically to allow children independence in the journey to refining them.

Not only were the children of this first Casa privy to the materials; they also were the first to experience Montessori practical life lessons. They helped to prepare and serve their own meals. They polished the silver and cut and arranged the flowers. They learned polite social norms through intentional modeling and lessons in grace and courtesy. They began to take pride in their work, their community, and their home. Montessori recruited a woman who was a resident of the complex to become the teacher, and the children’s mothers met with her regularly to discuss progress.

The results were astounding. This work done with the children slowly trickled outward so that it positively affected the entire neighborhood. Visitors came to the school and were amazed at how focused and engaged the children were with their work. No one had ever seen anything quite like it before.

Observing, Refining, and Sharing

Montessori’s work and ideas spread quickly as more and more people visited Casa dei Bambini. Requests were made to open new schools elsewhere, and Montessori soon found herself training teachers, producing copies of her materials, and giving lectures around the world.

Throughout her life, Dr. Montessori’s work never ended. Though she began with a focus on children aged 3-6, during different times in her life she focused on developing methods and materials for elementary aged children, infants and toddlers, and adolescents. She was a fierce advocate for the preservation of the methods she had worked tirelessly to create. She was, after all, a woman of science. Each material, each lesson, each approach - they were all a result of many hours of careful testing, observation, analyzation, and refining. It was understandably important to her that the movement that bore her name moved forward in a way that honored her high standards.

Montessori Education: Where It Stands Today

Today, there are tens of thousands of Montessori schools across the globe. In the United States alone, there are more than 2,000 private and more than 500 public Montessori schools.

Efforts are being made to advance Montessori into mainstream education while retaining high fidelity methods. Current scientific research in areas of learning, brain development, and human development are repeatedly confirming what has already been known by over a century of Montessori education.

What might the next decade bring? Shifts in our common goals for education and what developing children need just may be the push our society needs to fully embrace what’s been working for so many families for such a long time.

We’re glad to have you on this journey with us.

You might also like

19 Sep, 2022

Adolescents exist between two worlds: they are no longer children but they aren’t yet adults. On this bridge to adulthood, adolescents need opportunities to develop real, meaningful, adult-level skills. They aspire to do what adults do. They are curious about how to make their own way in the adult world. As adults, we are part of an economic system. Even if we aren't using money to buy something, through our work or our hobbies we produce or consume aspects of culture. In this way, economics is about the web of interdependence we have with other people. We all depend upon the work and activity of others. Economics and Interactions If we look at economics as how people offer value in their interactions, as well as the production, distribution, and consumption of services and goods, we can really think about economics as how we organize ourselves in society. Because adolescents are building the skills for stepping into the adult world, it’s important to consider how they are developing their ability to navigate this economic aspect of adult life. How many of us had the opportunity, as adolescents, to develop the skills necessary for economic independence? How would our lives be different if, as adolescents, we had a support system so we could Oigure out a fair and reasonable cost for goods we produced, faced the reality of a proOit and loss statement, or found our way in navigating the paths of spending, saving, and sharing? Road to Achieving Economic Independence Dr. Maria Montessori realized the importance of adolescents developing these kinds of skills. In From Childhood to Adolescence, Dr. Montessori made a bold statement about our approach to education and its impact on the greater society. She stated it clearly: “The essential reform is this: to put the adolescent on the road to achieving economic independence.” So in Montessori adolescent programs, we offer our emerging young adults the opportunity to learn key skills of production and exchange. We sometimes call this “microeconomy.” The basic idea is that adolescents need opportunities to produce goods and services, and work with money and monetary systems, so they can develop an understanding and appreciation for how economies work and their own role in economic systems. Real, Meaningful, and Purposeful Work This experience can take many different forms depending upon the community. Whether running a farm stand or a holiday marketplace, adolescents get to learn key skills. They learn to balance proOit and loss. They discuss and determine how much money should be reinvested into the business to help it grow or how much money should be reinvested in the greater community. They respectfully listen to their customers’ needs and concerns and incorporate that feedback in useful ways. In order to have these learning experiences, adolescents need real, meaningful, and purposeful work. Just like young children need to actually prepare food rather than play with a pretend kitchen set, adolescents need actual experiences in creating a business plan, keeping track of income on a spreadsheet, and balancing a budget. They need to practice accounting work so they can build the skills for their own economic independence. They need to have the thrill of handfuls of cash and then face the responsibility of keeping track of those earnings. They need the experience of paying for replacement materials when they have overused key supplies. If they have developed some savings and want to invest the money, they need to Oind opportunities that align with their values. Preparing for Adult Life Too many of our young people enter the world of adult lives without having experienced their role in an economy (perhaps other than being consumers!). Economic independence is a key part of preparing for adult life. We want our adolescents to step into maturity with conOidence that they can independently navigate their new responsibilities and roles. If we give adolescents the opportunity to learn how to have a sound basis for their economic decisions, imagine where they will be when they are adults and making decisions that affect broader aspects of society!

12 Sep, 2022

In their first weeks of life, babies begin to focus their eyes and track objects. These small acts of visual control provide an important foundation for newborns who are building their neural networks. To set infants up for success, we offer a series of specially designed mobiles to aid this development. Each Montessori mobile is created with particular characteristics to help babies further develop their sense of sight, depth perception, concentration, hand-eye coordination, and more. Plus, newborns love them! Essential Characteristics of Montessori Mobiles Montessori mobiles follow a progression that parallels infant development. The first mobiles have a visual focus and begin with basic shapes. They progress to include more complicated objects and eventually become interactive and tactile. The first mobiles are simple and light enough to allow them to flow with gentle air currents. In order for infants to have the best visual experience, a mobile should be hung so that it is about 12 inches in front of them rather than directly above. When babies are lying on their back, there should be a visual line at about a 45-degree angle from their eyes to the mobile. This particular placement allows infants to see the whole mobile moving. Each mobile has visual components designed to help infants track the objects and sharpen their vision. Then after these opportunities to follow objects visually, infants begin to have more arm and hand control and might begin to reach and grasp objects nearby. To support this new ability to reach and grasp, the mobiles take a slightly different form and thus need to be easy to grasp, colorful, and safe for children to mouth. Progression of Mobiles: Visual The first four mobiles–the Munari, Octahedron, the Gobbi, and the Dancers–provide babies with meaningful visual experiences when they are just recognizing shapes and then later identifying colors.

05 Sep, 2022

In Montessori, we talk a lot about independence. However, one of the lesser known or understood aspects of Montessori is that independence isn’t the end goal. As humans, we are each wonderful, unique individuals. But we don’t exist in isolation. We live amongst other wonderful, unique individuals! In order to effectively live in community with other people, though, we need to be able to function independently. Said another way, before we can offer help to others or make ourselves useful, we need to be able to meet our own needs. How can we be independent and interdependent at the same time? We all want to make choices for ourselves, exercise our liberty, and be responsible for our own lives. At the same time, we also want to be part of something. We are designed to be both independent and be in community. These two needs are not mutually exclusive, but in fact, operate in relationship to each other. We have an innate desire to be autonomous and to belong. When we develop the ability to act for ourselves, make choices, control ourselves, and accept responsibility, we are able to be functioning, contributing members of society. We can see what needs doing and do it because we have the skills to do so. We can work with others to create solutions or produce goods and services. We can be part of a community by acting and taking responsibility for our actions, each able to contribute because we all have the skills to do so. What does this have to do with children and Montessori education? From a very young age, children are trying to exert control over their lives. Children are trying to gain functional independence from birth to about age three. In Montessori classrooms, we offer all sorts of opportunities for young children to develop skills that help them take care of their basic needs. But we don’t stop there! We also provide so many ways children can care for others and for their surroundings. Once children have mastered pouring from one pitcher to another, they are able to pour water into a vase and arrange flowers to beautify the classroom. After they learn how to sweep, they are quick to notice a spill and rush to get the dustpan and dust brush so they can help. When someone is struggling to zip their jacket, they take pride in sharing their newfound skill in service to someone else’s need. As children move into the elementary years, this service to others often takes on a slightly different form, in part because elementary-age children are developing their intellectual independence. Thus, their contribution often involves applying these newfound intellectual skills. They might notice a classmate struggling to figure out the steps in a math problem and offer support. Or when friends are in conflict, they might provide some mediation to help each party listen to the others’ perspective. In adolescence, young adults are ready to work toward being socially and economically independent. They want to figure out their place in society, grapple with real problems, and contribute in a useful way. Thus, Montessori adolescent programs offer teens the chance to develop and feel secure in their own abilities while also collaborating in real and meaningful social endeavors. In the process of running a small business, for example, adolescents are applying their intellectual skills from marketing to mathematics, while also navigating how to communicate with customers and collaborate with classmates. Why is this important? As humans, we want to achieve independence and belonging. Being independent is about learning the skills to be able to contribute in a meaningful way. All the little conquests of independence–throughout each age and stage of development–matter! When our infant reaches to grasp an object, our two-year-old demands to put their shirt on themselves, our eight-year-old argues about just and fair rules of a game, or our adolescent insists they can solve a problem with their peers, we can remember that these acts of independence are laying a foundation for our children to become part of an interdependent, harmonious society. Independence is just a step. Interdependence is the ultimate goal.